As Stubble To Our Sword

Oliver Cromwell’s letter to Colonel Valentine Walton, 1644

The English Civil Wars were not a topic taught in Canadian high schools when I was a teen, but I do remember stumbling on the 1970’s movie “Cromwell” (starring Richard Harris and Alec Guinness) one afternoon while channel surfing between A&E, Bravo, and The History Channel. I was fascinated. That was my first encounter with the subject matter. My second was when Nuts! Publishing sent me a copy of This War Without An Enemy.

So when I tell you I have only a rudimentary grasp of the history presented here, please know that even this is probably an overstatement. I understand the broad strokes of the first English Civil War, but it’s a complicated matter and I’m definitely no expert. What I do have is a keen interest in learning more about it. I’ve even picked up a couple of other games about the English Civil Wars since learning this one – like the wonderful Cruel Necessity (Victory Point Games), and the criminally difficult to find Unhappy King Charles! (GMT). I’ve also got The English Civil War: A Military History by Peter Gaunt on my reading list.

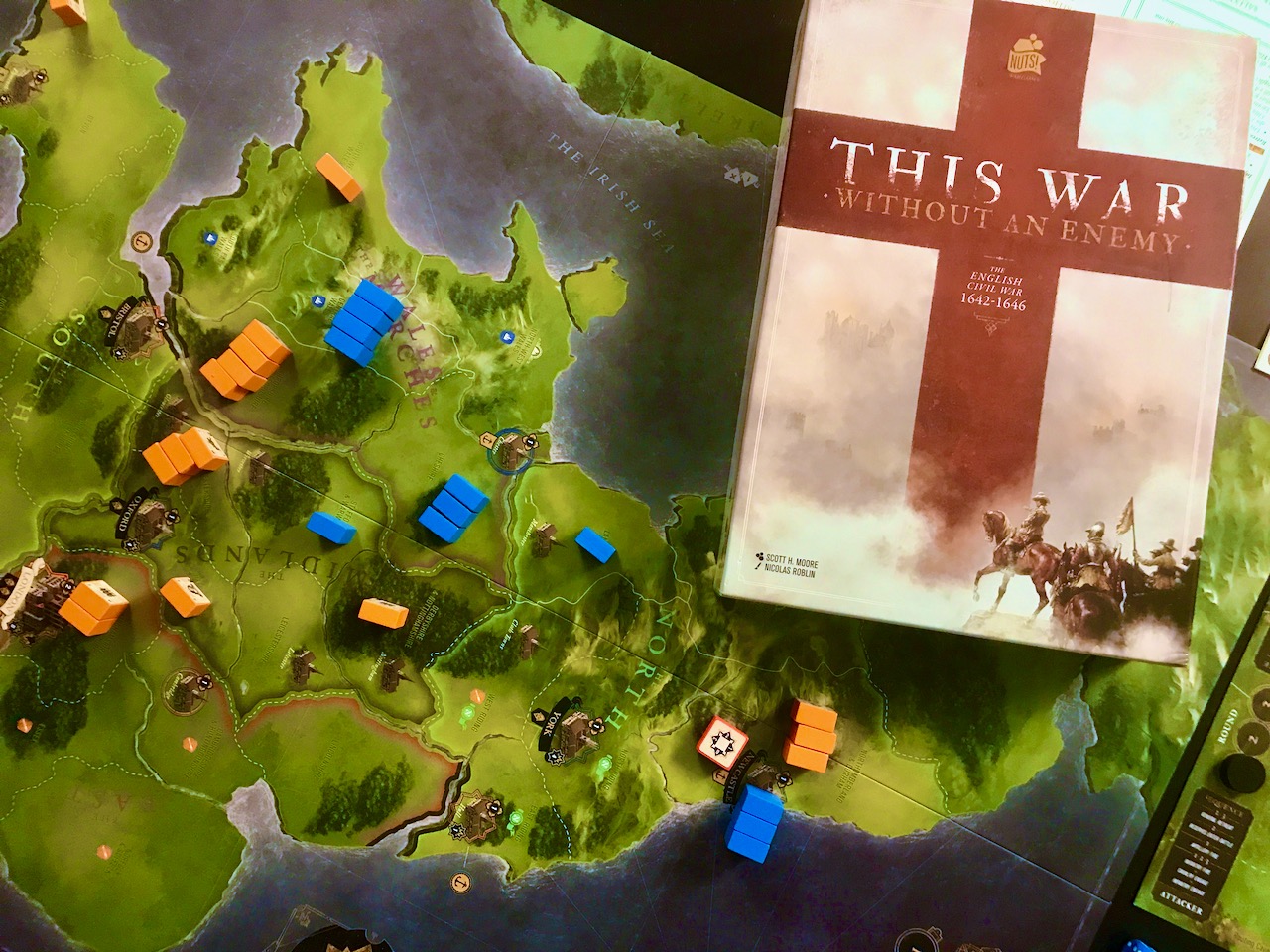

Scott Moore, the designer of This War Without An Enemy, has spoken in interviews about how he originally designed it as a Columbia block game, but it languished in development for some time before Scott decided to shop the idea around and got it picked up by Nuts! Publishing. That proved to be a good thing because while this game certainly has its roots in Columbia’s block system, it turns up the volume to 11, and Nuts! has matched that effort with their terrific production quality. Artist Nicolas Roblin’s work here is spectacular, from the board to the blocks to the box… it’s a beauty. The flourishes and graphics are sharp, pretty, and easy to ready. It really is a masterclass in boardgame visual design.

Okay, so what is This War Without An Enemy about? I won’t turn this into a history lesson, since that would be pretty short and questionable coming from me, but I’ll do a brief recap. The English Civil Wars took place between 1642 and 1651 and are divided into three distinct wars. They are actually a part of an even wider conflict known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which encompass conflicts that arose in Scotland and Ireland as well as England.

This game focuses on the first English Civil War, from 1642-1646. King Charles I of England had much earlier imposed personal rule, giving himself the power to rule without having to answer to parliament. Parliamentarians were not entirely anti-monarchist, but they didn’t like that the King held so much unchecked power. They wanted a constitutional monarchy. So began the bloodshed.

This War Without An Enemy is a card-driven block wargame. Blocks represent cavalry, infantry, or artillery, and each has pips along the edges of the blocks (similar to other block wargames) representing their effectiveness. Some blocks represent leaders, who grant certain bonuses to the units that are with them. The game is a victory point tug of war. Points come from cities, and for the Parliamentarians by potentially capturing the King, even offering a potential instant win for the Parliamentarians if the King can be captured before the Royalists take any cities. That’s a tough ask though.

The Parliamentarians start with a 1 VP advantage, but the Royalists have slightly better units to start, so it’s in the interest of the King for that side to come out aggressively early on, and for the Parliamentarians to hang on until they get access to their better units.

Each turn, players choose a card from their hand of six and this is played by both sides simultaneously and revealed at the same time. That card offers action points, which also determine who goes first. In the case of a tie, the Royalists choose. Action points work similar to other Columbia block games, and will let you move units around, muster, or reinforce units.

Movement is perhaps my biggest gripe with This War Without An Enemy, and that’s mostly because of the complexity and caveats. Generally speaking, you pick a location and the blocks in that location can move two spaces out. However, if you want to move blocks into a location with an enemy, there are border restrictions that will limit how many blocks can enter, depending on the type of border. If you’re clever you might be able to move “around” the restriction to end up in the same place, since you can move two spaces. Regional blocks can only moving outside their home region if accompanied by a leader or regional leader, but they can re-enter their home region without a leader or regional leader. There are also sea moves… and while all of this makes perfect sense, there’s just a lot to remember.

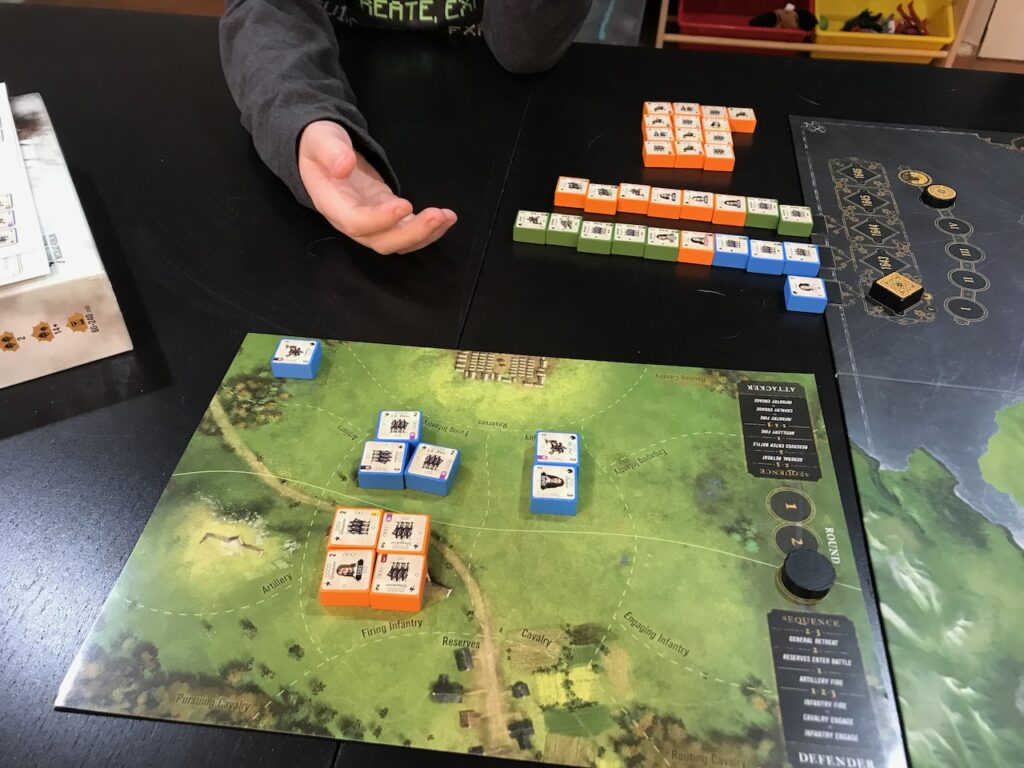

Combat is an interesting affair, and perhaps the part that stands out the most from other block games I’ve played. It’s handled over 3 rounds (maximum) on a battle mat which looks topographical but acts entirely as a player aid to determine the phases of combat and manage reinforcements. The pips remaining on the block indicate how many dice they roll in combat, and the number on the block indicates what they are aiming to roll. If they want to fire muskets, they get to roll and inflict their damage before melee, but their chances to hit are reduced. Retreats are available in rounds 2-3 of combat but it’s not immediate, and both sides suffer to-hit penalties. Battles are a sticky bloody affair, and can be quite elaborate if there are a lot of units and reinforcements involved – but they are handled quite elegantly here, and I think a lot of that is thanks to the excellent mat.

Sieges are also a frequent affair, and while a chunk of the rulebook is devoted to sieges, they aren’t too difficult to parse. Entering an area with an enemy unit and a town allows the enemy unit to fall back (withdraw) into the town. Besieged units may sally out from a siege to face the enemy on the field, or besiegers can choose to storm a city, but often times a besieger will just sit outside the walls and starve the inhabitants.

It all feels very period accurate and evocative of the era. I’m not sure if that should be attributed to the lush visuals or the game system itself, but I’d venture a guess that it’s a combination of all of it.

Overall, I really enjoyed This War Without An Enemy and I think a lot of that is due to the audaciousness of the game. Scott took the core elements of block wargames and expanded upon them in a way that created a new creature – one that feels like an evolutionary step for the genre. I do think the movement rules could have been streamlined or pared down in some way, but I don’t feel like that’s a indictment of the game – just a mild criticism on what is otherwise a very slick and compelling package. Anyone who has even a passing interest in this time period should go out of their way to play this one.

Review copy provided by the publisher.